从写作到“闲聊”,或为何《JURNAL KARBON》不再发表文章而在播客上聊天:一次反思

- Berto Tukan

- 2025年6月28日

- 讀畢需時 12 分鐘

已更新:2025年8月3日

在2014年末或者2015年初到年中左右(我记不清具体时间了),一个平常的傍晚,在位于雅加达南部的特贝特东内大道(Tebet Timur Dalam Raya)6号,阿尔迪·尤南托(Ardi Yunanto)和法里德·拉昆(Farid Rakun)约我聊天。为了这次会议,我准备了一份进度报告,内容是我对雅加达火车站附近属于市民的停车位的研究和写作过程。这份研究和写作将发表在karbonjournal.org上。我们坐在ruangrupa空间后屋的一张长桌边。在OK录像室和事务室中间的小花园里,一尊陷入冥想的佛像正盯着我。在我陈述完后,阿尔迪说:“别管这些了,我们希望你来负责《Karbon Journal》。”我想:“嗯,再说一次?”

正如文章标题和上面这个小故事所指明的,这篇文章是关于《Jurnal Karbon》的———具体来说,是近十年以来,我作为《Jurnal Karbon》的一部分的经验和对它的理解。因此,本文将结合档案数据和我脑中的回忆,而不会在意资料精准性和主观感受之间的差距。

《Jurnal Karbon》名字里“Journal”这个词经常被误解。“Journal”本身与严肃的学术出版物有关。如今,印尼的学者遵循一套特定的科学写作规则,外加一套据说可以表明期刊质量和可信度的认证系统。因此,当与不熟悉《Jurnal Karbon》及其母组织ruangrupa和“Gudskul生态系统”的人聊天时,误解常会出现。比如,人们会问“你的刊物有什么认证?”“你们的Sinta[1]等级是多少?”等等。为了避免这种情况,让我先简单介绍一下《Jurnal Karbon》。

四种定义与《 [Jurnal] Karbon》

《Jurnal Karbon》由ruangrupa于2000年创立,这也是这个团体诞生的那一年。最初,杂志的出版意图是:

……作为ruangrupa所有活动的输出媒体,触达更广泛的观众、激发辩论和讨论。该杂志聚焦与ruangrupa的艺术项目、文献和研究相关的艺术与文化类文章。这对印尼艺术批评家的发展也非常重要,因为很长时间以来这里一本艺术(尤其是视觉艺术)类刊物都没有(上一本艺术杂志出版于1948年,名为《艺术人》[2])。

看起来《Jurnal Karbon》被设想为:(1)自我批评的工具,以及(2)传播知识的尝试。后者由于印尼当时不太理想的知识交流环境而变得困难。

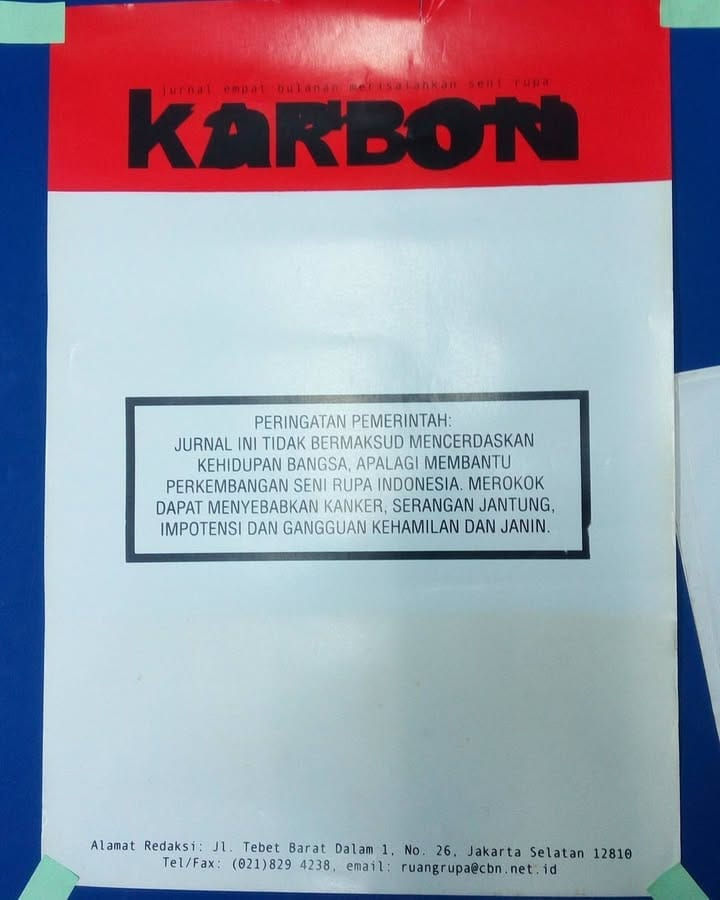

如果你今天尝试去查找《Jurnal Karbon》的现状,你可能只会找到(1)它的社交媒体账户Instagram,(2)一些隐藏在rururadio播客账户中的播客。仅此而已。在《Jurnal Karbon》目前的Instagram页面上,可以找到它的第四版自我定义:“《Jurnal Karbon》是一本由ruangrupa发起的关于当代艺术和城市研究的多学科杂志。”这个定义经历了许多变化,并且在持续改变。以第一个版本为例,《Jurnal Karbon》2001年第2期至4期上写着的定义是:“一本有关艺术话题的季刊”[3]。而ruangrupa的15周年纪念小册子(在2015年出版)中有一个不同的定义(即第三版):“……一份线上杂志,以创造性、批判性和具有想象力的方式,从不同角度讨论印度尼西亚城市居民的公共空间、作品和视觉文化等议题。”[4]

从十到十五年间的四个版本的自我定义中,我们可以看到杂志如何不断更新其范围和重点。2001年的定义(第一和第二版)强调艺术,并关注ruangrupa自己的项目、记录和研究。在2015年的定义(第三版)中,重点略微转向城市视觉文化[5]。在当前的定义(第四版)中,我们看到了合并这两种趋势的尝试。定义的更迭与《Jurnal Karbon》从印刷到数字和基于网络的格式变化是一致的。同时,最新的定义呼应了《Jurnal Karbon》对其他媒体的使用。为了更清楚地展示格式的变化和定义的转变,以下是一条时间轴:

在以上的时间轴中,我收录了《Jurnal Karbon》和另外两本相关作品:第一个是《雅加达城市空间中的公共和广告牌》( Publik dan Reklame di Ruang Kota Jakarta,2013年),这是一项《Jurnal Karbon》和印度尼西亚法律与政策研究中心的合作。

第二本是《Majalah Bung!》。《Majalah Bung!》并没有直接由《Jurnal Karbon》出版。然而,我认为这本杂志很重要,因为它是ruangrupa书面作品的延伸[6]。同样有趣的是,《Majalah Bung!》出现在《Jurnal Karbon》从印刷品改为在线杂志并更名为“karbonjournal”之后。这一变化回应了(特别是在当时的印度尼西亚)日益普及的互联网,以及许多基于互联网的大众媒体的出现。ruangrupa的成员大多出生在90年代。在经营了几年的线上杂志后,他们开始怀念实体格式。更具体地说,他们怀念纸质杂志作为信息和愉悦的主要来源的日子——这对他们这一代人来说无疑如此。阿尔迪·尤南托,《Majalah Bung!》的总经理及karbonjournal.org的编辑之一,在他为《Majalah Bung!》撰写的告别文章中坦白了这一点:

无论如何,最后一代数字移民需要顺应潮流。因此,我们对杂志最怀念的可能不是信息的速度和全面性,也不是身份认同的稳固化——这些都很容易被谷歌、免费下载网站、在线大众媒体和社交媒体提供。我们最怀念的是那些诚实、新鲜、勇敢、顽皮也有意义的文章、照片和插图,它们用着生动的印度尼西亚语,在尊重新闻原则的情况下,挤在一堆纸页里,读起来有趣,也不用急着看完。[7]

作为一名写作者,我第一次与ruangrupa的书面作品的互动也是通过这本杂志。幸运的是,我当时写的并不是狭义的艺术和文化。我受一位朋友罗伊·塔尼亚戈(Roy Thaniago)的邀请(他也是《Majalah Bung!》和karbonjournal的编辑成员),为杂志最后一期的“Nasihat Ayah”(父亲的建议)栏目撰稿。

回到上面的时间轴,在2000年至2013年间,《Jurnal Karbon》似乎并不总是生产包含研究论文或者特定科学分支的专著的传统期刊。从2014年至今,情况也是如此。[8]《Jurnal Karbon》已经扩展到包括视频、展览、播客、广播和研究。因此,在它的发展过程中,《Jurnal Karbon》不再仅仅是一个通过写作传播知识的媒介。不仅如此,它还成为探索知识生产和传播的种种可能性的平台。

关于《Jurnal Karbon》之旅的最后一点说明,也将我们带入本文的下一个话题,是关于找作者的困难。至少在我为《Jurnal Karbon》工作的十年里,我感受到了这一点。因为你现在可以很容易地在谷歌上找到信息,写作和阅读不再是许多印尼人的活动选择。定期发表每周的写作很难,通常需要编辑自己动手才能达到出版目标。此外,读者很少回应,尤其很少出现能引发讨论的写作回应。这种情况是我们在rururadio广播上发起脱口秀节目并将其作为播客发布的动力之一。好消息是,以这种方式,我们可以确保节目每周更新。根据我们的经验,每周都要找到采访对象并不算难事。显然,口传传统在我们的语境中更加奏效,而且这项选择其实很不错。

沉默之路

上述的最后一个问题引发了我的另一番思考。在印度尼西亚,越来越少的人喜爱阅读和写作,这影响了《Jurnal Karbon》的工作。《Jurnal Karbon》最初被设想为一种通过写作来生产和传播知识的手段,正如它的第一和第二种定义所示。这种普遍的困境当然不仅仅是《Jurnal Karbon》在承受着。相反,所有在印度尼西亚致力于写作的人都经历了同样的事情。[9] 印度尼西亚作家和知识分子长期以来一直认为,他们选择的实践是一条“忠于沉默之路”。[10]

当然,这是由几个相互关联的因素形成的。这里可以提到的两个方面是经济和教育。经济原因很简单,一个人通过写作赚的钱很少。我记得与印度尼西亚资深视觉艺术作家班邦·布佐诺(Bambang Bujono)的一次对话。当时,我们试图计算一名自由撰稿人从印度尼西亚一家知名出版物获得的酬金(当然,这是薪酬最高的出版物之一)。然后,我们将它与雅加达的作家想要参观万隆的展览所需要的费用进行比较。我们的结论是,酬金甚至无法足够支付住宿和交通。

印尼的现代教育自诞生之初,在其所设定的终极目标上就是自我否定的。对迈克尔·J·桑德尔(Michael J. Sandel)来说,大学层面的教育目的仅仅是为了尊重和奖励学术上的卓越表现,并通过在社会中树立榜样和建立理想或思想来履行对社会的责任。[11] 印度尼西亚的现代教育最初是由荷兰殖民者在“政治伦理”(Politik Etis)的背景下广泛推行,但它从一开始已经违背了这一目的:他们的目标非常实际,即在群岛培养廉价劳动力。对当时的许多印度尼西亚人来说,有机会接受教育,然后在荷兰的办公室当职员,是提高社会地位的一种方式——成为“贵族”(priyayi)[12]。因此,人们对教育产生的头衔和教育机构本身更感兴趣,而不是他们获得的知识。“重要的是尽快毕业,拿到文凭,然后找工作。”我们经常听到这样的笑话。这种扭曲的教育目标今天仍然存在。下面这段马丁·苏里亚贾亚(Martin Suryajaya)的引述或许可以说明印度尼西亚教育机构的状况:

我们有机构,但它们只是伪机构:它们有时扮演教育机构,有时扮演银行,有时扮演礼拜场所,有时扮演腐败的巢穴,有时扮演玩多米诺游戏(gaple)的地方。没什么是确定的,也没有人确切知道。[13]

问题是,为什么会发生这种情况?上面我们谈了一点殖民主义带来的现代教育目标的扭曲。马丁·苏里亚贾亚和希尔玛·法里德(Hilmar Farid)推测这条“沉默之路”起源于殖民主义导致的印度尼西亚写作和学术背景。[14] 殖民主义不仅在非物质文化层面,也在物质文化层面,造成了文化断裂。

让我们对此进一步研究。我们将从小说《来自Oetimu的人》(Orang-Orang Oetimu)中一段有趣的摘录开始。这部小说讲述了从葡萄牙殖民时期到印度尼西亚独立的几十年间,印度尼西亚地区的帝汶岛上一个名叫Oetimu的村庄的故事。其中一个角色是Am Siki,他拥有特殊的帝汶魔法。他用他的魔法一度杀死了许多日本士兵,因为日本兵强奸了他的马。以下是Am Siki在小说中的抱怨之一:

接着,Am Siki的胸口紧绷了起来。他伤心了,因为外国人来了又来,但其中没有一个人想学会正确地说那种语言。总是帝汶人被迫学习从他嘴里发出的奇怪声音的含义;从葡萄牙语、荷兰语、日语到印度尼西亚语。[15]

从Am Siki的悲伤中,我们可以看到殖民主义如何剥夺了人们的语言——这是人们传播知识的主要工具。在Am Siki的背景下,帝汶人不得不放弃他们的语言,并学习新的语言。事实上,正是通过自身的语言,人们才能理解周遭的世界,并构建起他们的社会生活方式。当他们习得一门外语,并慢慢忘记自己的母语时,他们就失去了对他们自己世界的知识。

在知识界的背景下,正如希尔玛·法里德描述的那样,阿米尔·哈姆扎(Amir Hamzah)叙说了随着殖民主义的到来而消失的马来传统诗歌“班顿”。剩下的只有“沉默”:“马六甲被阿方索的大炮摧毁后,马来诗人的精神消失了。马来孩子的胸膛里的寂寞,熄灭了诗歌的火焰,擦干了诗的眼睛。”[16] 所有的文学(智性工作)的精神都随之消逝,因为灵感和文化的源泉也被殖民主义摧毁了。例如,1894年,荷兰人袭击龙目岛,掠夺了成百上千的珍宝和古代手抄本。[17]

马丁·苏里亚贾亚在他的书《文学,毁灭》(Kesusastraan Kehancuran)中进一步论述了这个问题。他认为这是印度尼西亚文学从殖民时代到现今总会出现“寂寞”这个意象的原因。殖民者甚至改变和编辑了群岛的文化,随着时间的推移,这些文化被认为是群岛本身的原始文化。苏里亚贾亚说:“我们今天所说的‘传统’,其实是为殖民利益而建构的一种对过去的模拟。”[18] 起初,印度尼西亚的知识分子只是感受到了沉默,但没有意识到这一点。根据苏里亚贾亚的说法,印尼国民作家普拉姆迪亚·阿南达·杜尔(Pramoedya Ananta Toer)是那些意识到沉默背后——在“沉默的歌声”背后——的原因的人之一。普拉姆迪亚通过他的著作《沉默的独白》(Nyanyi Sunyi Seorang Bisu)表明,“沉默”是殖民主义和新殖民主义带来的影响。[19]

同样重要的是殖民主义如何改变了知识传播的媒介。在马来群岛文化(Nusantara)手抄本被毁之后,殖民者引入了包含它自身“组成部分”的现代西方教育。群岛上的字母被罗马字母取代。这改变了学习的方式,学习由传统中坐在一起的交流转变为一种冰冷的、单向灌输式的课堂。当然,像口语一样,某个特定社会使用的书写系统也根植于其自然和社会条件。知识传播中不熟悉的部分和媒介也会影响获取知识的具身过程。我在本文开篇抱怨的对于写作和阅读活动的缺乏重视,或多或少是受到了强制推行的书写系统产生的影响。

回到《Jurnal Karbon》的命运

以上的历史故事如何有助于反思《Jurnal Karbon》的历程?前面提到过,《Jurnal Karbon》本身并不是一个知识传播工具。将之视为一种在不同知识传播媒介上进行实验的努力更为准确——从印刷期刊到网络杂志、视频和电台聊天等形式。但如果我们翻阅该期刊的六期纸本刊物,会发现一种与今日《Jurnal Karbon》所做的电台聊天相似的写作形式。在这六期的每一期中,你总能找到一份关于某一特定主题的讨论或谈话的转录稿。可以说,这本杂志从一开始就关注这些对话。在不知不觉中,当《Jurnal Karbon》近年来愈发专注于通过电台广播传递谈话时,这种对对话的强调再次浮现。

也有可能——这当然仍属推测——群岛的口述传统以更深刻的方式向它的人民对话。是现代教育让我们忘记并远离了它。诸如网络广播和播客等平台的兴起,或许重新唤起了类似于口述传统的知识传播可能性。人类最初发明文字,不是为了让它能永恒不变地流传下去吗?在口述传统中,知识的传承依靠一代代口耳相传,其特性恰恰在于传递过程中可能产生的诸多变异。而如今的录音与播客技术,实际上消除了这种变异的可能,使口头语言得以在任何时间、任何地点被聆听。

到2025年,ruangrupa将年满25岁。《Jurnal Karbon》也是如此。最近,《Jurnal Karbon》一直处于停刊状态,安静地休息,只是偶尔发布新材料。迪尔多·阿迪迪约(Dirdho Adithyo)、巴古斯·普尔沃阿迪(Bagus Purwoadi)、阿尤·毛拉妮(Ayu Maulani)和我,目前在《碳杂志》工作的四个人,把我们大部分的精力都花在Gudskul生态系统的其他工作上。《Jurnal Karbon》似乎在独自坐着,等着我们再次修补它。这篇文章只是回忆的溢出和翻阅现有档案的结果。它可能是一种反思,它可能是一个问题,它可能是一个进一步改变的开始。或者,它也不会产生任何东西。

本文由迪尔多·阿迪迪约首次编辑与校对。

英文第二轮编辑:黄梓耘

翻译:邹健仪、聂小依

翻译校对:刘菂

注释 Notes

[1] Sinta是由教育和文化部颁发的杂志认证制度。请参阅https://sinta.kemdikbud.go.id/,2024年12月17日访问。

[2]罗尼·奥古斯丁等人编辑,《Absolut Versus》(雅加达: ruangrupa) ,2001年,第53页。我不确定印尼的最后一本艺术杂志是否是《艺术人》。也许当ruangupa的早期成员写《碳杂志》的描述时,他们并没考虑艺术学院的“学术期刊”。也可能是当时学术界还没有艺术期刊。即使有,有时学术刊物与学术界之外的实践也没有太多联系。至于上面引用的说法的精确性,还需要再做研究才能确定。

[3] 《Karbon》 (Cetak城市版)。 2001年第四期,第二版印刷,第2页。

[4] 阿尔迪·尤南托 等(Ardi Yunanto et al.),《Ruangrupa 2000–2015》,雅加达:ruangrupa,2015年,第11页。

[5] 这并不意味着《Jurnal Karbon》完全独立于ruangupa的工作。从最早期到现在,这种联系一直是不可分割的。我在这里的意思是,定义的重点已经转移了。

[6] 当然,ruangrupa的书面作品并不局限于这篇文章所提到的。还有许多其他书籍、目录和网站都是由runangupa制作的。在这篇文章中所呈现的是,在我看来,与《Jurnal Karbon》最相关的文章。

[7] 阿尔迪·尤南托,“Hai, Bung!”,《Bung!》,第四版,2012年12月至2013年1月, 第103页。

[8] 在这个时间轴上,有一个《Jurnal Karbon》的项目被遗忘了,也就是2015年《Jurnal Karbon》和Qubicle合作的视频报道项目“Tak Kenal Maka Tak Sayang”(马来谚语,意为“不知道就不会爱”)。视频中讨论了不少于10个关于艺术及其生态系统的报道和闲谈视频。这些视频展示了黄道十二宫的小故障对艺术创作的影响。

[9] 我要在这里强调,这并不意味着我认为其他国家的情况更好。然而,由于对其他国家类似问题的了解有限,我把注意力放在了印度尼西亚。

[10] 当然,这并不适用于所有类型的作家和所有类型的写作;有某些类型的写作非常有市场,也有某些作家可以走高速公路。

[11] 迈克尔·J·桑德尔,《正义:什么是正确的事?》(纽约:Farrar, Straus and Giroux)2009,第191 –192页。

[12] “Priyayi是属于社会某个阶层的人,他们的地位被认为是可敬的,比如公务员。”KBBI在线,于2024年12月18日访问。

[13] 马丁·苏里亚加亚(Martin Suryajaya),《重返德里雅尔卡拉:校友返校活动手册》(Homecoming Alumni STF Driyarkara: Buku Program),雅加达:德里雅尔卡拉哲学院(STF Driyarkara),2019年。

[14] 参见:希尔玛·法里德(Hilmar Farid),《寂静作为前殖民地国家文学的核心母题》,载于 尼杜帕拉斯·厄尔朗(Niduparas Erlang)编,《研讨会:后殖民与当代跨学科议题》(楠榜卡西比东:勒巴县教育与文化局,2018年);以及 马丁·苏里亚加亚(Martin Suryajaya),《文学,毁灭》(雅加达:Velodrome 出版社,2024年)。

[15] Felix K. Nessi, Orang-Orang Oetimu. (Jakarta: Marjin Kiri). 2022, p. 39.

[16] 希尔玛·法里德,《寂静作为前殖民地国家文学的核心母题》(Kesunyian sebagai Motif Utama Kesusastraan di Negeri Bekas Jajahan),第2–3页。

[17] 希尔玛·法里德·塞提亚迪(Hilmar Farid Setiadi),“重写国家:普拉姆迪亚·安纳塔·图尔与非殖民化政治”。博士论文,亚洲文化研究项目,新加坡国立大学,第74–82页。

[18] 马丁·苏里亚加亚,《文学,毁灭》,第104页。

[19] 马丁·苏里亚加亚,《文学,毁灭》,第125页。

作者

Berto Tukan是雅加达 Gudskul Ekosistem 的成员。他是一名居住在雅加达的作家和独立研究者,同时也是 Jurnal Karbon的一员。2019至2021 年,他与 Gudskul Ekosistem 的几位朋友一起研究了印度尼西亚艺术团体的发展情况。这项研究的成果发表于《2021 年的艺术修复者:对过去十年印尼艺术团体的评估》(Yayasan Gudskul Studi Kolektif,2021年)一书中。他的短篇小说集《Seikat Kisah Tentang yang Bohong》于 2016 年出版,他最近出版的一部诗集是《Aku Mengenangmu dengan Pening yang Butuh Panadol》(2021 年)。

本文图片均由作者提供。

感谢吴作人国际美术基金会对本文稿酬的支持。

感谢通过“赞助人计划”支持《歧路》的个人与机构。

留言