From Writing to 'Blabbing', or Why Jurnal Karbon Doesn't Publish Articles Anymore But Talks On The Radio: A Reflection

- Berto Tukan

- Jun 27, 2025

- 14 min read

Updated: Aug 3, 2025

One ordinary evening at Jalan Tebet Timur Dalam Raya No. 6, South Jakarta, around late 2014 or early to mid-2015 (I can't really remember the time), Ardi Yunanto and Farid Rakun invited me to chat. For the meeting, I prepared a progress report on the research and writing process about citizen-owned parking lots around train stations in Jakarta. The research and writing will be published on karbonjournal.org. We sat at a long table in the back room of ruangrupa's house. The meditating Buddha sculpture in the small garden between OK. Video room and the Admin Room was staring at me. After I finished presenting the report, Ardi said: 'Forget it, we want you to be the one who takes care of Karbon.' Me, huh, come again?

As made clear by its title and the brief story, this article is about Jurnal Karbon—more specifically, my understanding and experience as a part of it for about a decade. The article will therefore combine archival data with memories from my head. It will not be concerned with the gap between data accuracy and subjective feelings.

The word 'journal' in Jurnal Karbon is often misunderstood. 'Journal' itself is associated with a serious, academic publication. These days, Indonesian academics follow a certain set of scientific writing rules, coupled with an accreditation system that is said to indicate the quality and credibility of a journal. As a result, misunderstanding arises when talking about Jurnal Karbon with those unfamiliar with it and its parent organisation, ruangrupa and Gudskul Ekosistem. For example, people ask 'What accreditation does your journal have?', 'What Sinta[1] rating have you received?', etc. To at least avoid this, let me start with a little introduction about Jurnal Karbon.

Four Definitions and the [Jurnal] Karbon Journey

Jurnal Karbon was established by ruangrupa in 2000, the year when the collective was born. Initially, the journal was published with the intention to be:

...an output media for all ruangrupa's activities, to reach and stimulate debate and discussion among broader audiences. The journal focuses on art and essays on culture that relate to the art projects, documentation, and research of ruangrupa. It is very important as well for the development of Indonesian art critics in general because there has not been an art journal [visual art especially] published since a long time ago [the last art journal which was published was in 1948 called 'Seniman'[2]].

It appears that Jurnal Karbon was conceived as (1) a tool of auto-criticism as well as (2) an effort to disseminate knowledge. The latter was made difficult by the less-than-ideal environment for knowledge exchange in Indonesia at the time.

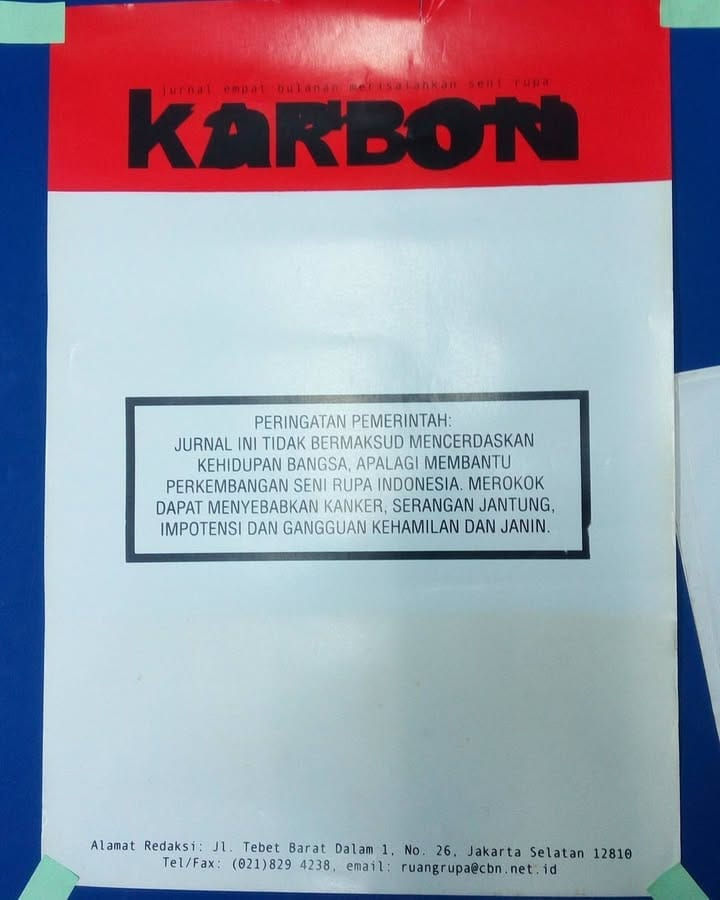

If you try to look up Karbon's current existence today, you will probably only find (1) its social media account Instagram and (2) some podcasts tucked inside the rururadio podcast account. Nothing more. On the current Instagram page of Jurnal Karbon, the fourth version of its self-definition can be found:'Jurnal Karbon is a multidisciplinary journal about contemporary art and urban studies initiated by ruangrupa'. This definition has gone through many changes and continues to shift. Take, for example, the first version found in Karbon issue 2 - 04 / 2001: 'A quarterly journal of art issues'[3]. A different definition (the third version) is found in ruangrupa's 15th-anniversary booklet (published in 2015): '...an online journal that discusses issues of public space as well as the work and visual culture of urban residents in Indonesia seen from various perspectives in a creative, critical and imaginative manner.'[4]

From the four versions of self-definition, spanning ten to fifteen years, we can see how the journal has kept updating its scope and focus. The 2001 definitions (the first and second) emphasised art and focused on ruangrupa's own projects, documentation and research. Then the focus shifted slightly to urban visual culture in the 2015 definition (the third definition)[5]. In the current definition (the fourth definition), we see an attempt to merge these two tendencies. This change of definition is in line with the change of Jurnal Karbon's format, from print to a digital and web-based format. Meanwhile, the latest definition echoes the utilisation of other media by Jurnal Karbon. To demonstrate the change of format and the shift in definition more clearly, below is a timeline:

In the timeline above I have included both Jurnal Karbon and two other works that are part of it. The first is the publication of the book Publik dan Reklame di Ruang Kota Jakarta (Public and Billboards in Jakarta's Urban Spaces) (2013), a collaboration between Jurnal Karbon and Pusat Studi Hukum dan Kebijakan Indonesia (The Indonesian Center for Law and Policy Studies).

The second is Majalah Bung! (Bung! Magazine). Majalah Bung! was not directly published by Jurnal Karbon. However, I think this magazine is important as an extension of the written work that emerged from ruangrupa. What is also interesting is that Majalah Bung! emerged after Jurnal Karbon changed from a print journal to an online journal with a new name, karbonjournal. This change was a response to the increasing use of the Internet, especially in Indonesia at that time, and the emergence of many Internet-based mass media. After a few years of running an online journal, members of ruangrupa, who are mostly born in the 90s, started to miss the analogue format. More specifically, they missed the days when physical magazines were a dominant source of information and pleasure, which was certainly the case for their generation. That's what Ardi Yunanto, general manager of Majalah Bung! and one of the editors of karbonjournal.org, confessed in his farewell article for Majalah Bung!:

This last generation of digital immigrants needs to go with the flow anyway. What we miss most about a magazine, then, is probably not the speed and comprehensiveness of information or the hardening of identities—which are readily served by Uncle Google, free download sites, online mass media and social media. What we miss most are articles, photos, and illustrations that are honest, fresh, brave, naughty, and also make sense, in lively Indonesian, packed in a bundle of pages with respect for the principles of journalism, which are fun to read without rushing to be finished quickly.

My first interaction—as a writer—with the written work of ruangrupa was also through this magazine. Happily, I wasn’t writing about art and culture in the narrow sense at the time. I was invited by a friend, Roy Thaniago, who was also a member of the editorial board of Majalah Bung! and karbonjournal, to write for the last issue of the magazine under the section Nasihat Ayah (Father’s Advice).

Returning to the timeline above, between 2000 and 2013, it appears that Jurnal Karbon didn't always produce conventional periodicals containing research writings or treatises from a particular branch of science.[8] From 2014 to the present, this has also been the case. Jurnal Karbon has expanded to include videos, exhibitions, podcasts, radio broadcasts and research. Thus, in its development, Jurnal Karbon is no longer just a medium for distributing knowledge through writing. More than that, it has become a platform for exploring the possibilities of knowledge production and distribution.

One final note about the Jurnal Karbon journey, which also brings us to the next topic of this article, is about the difficulty in finding writers. I have felt this at least in the 10 years that I have been with Jurnal Karbon. Because you can now easily find information on Uncle Google, writing and reading are no longer activities of choice for many people in Indonesia. It is very difficult, for example, to publish weekly writings regularly. Often, it is the editors themselves who need to step in to meet the publication quota. In addition, readers rarely respond, especially in the form of writing that can generate discussions. This condition was one of the drivers for us to initiate a talk show program on rururadio and publish it as a podcast. The good news is, this way we have been able to ensure weekly updates for the programme. In our experience, it wasn't too difficult to find interviewees every week. Apparently, the tradition of oral knowledge distribution is more effective in our context. And that was not a bad choice at all.

The Silent Path

The last problem above leads me to another reflection. The condition that increasingly fewer people in Indonesia like to read and write has an impact on the work of Jurnal Karbon, which was originally intended as a means of producing and disseminating knowledge through writing, as illustrated in its first and second definitions. This general dilemma is certainly not the fate of Jurnal Karbon alone. Instead, all those who dedicate themselves to writing in Indonesia will have experienced the same thing.[9] Among Indonesian writers and intellectuals, it has long been recognised that the practice they've chosen is one of 'being faithful to the silent paths'.[10]

Of course, this is shaped by several interconnected things. Two that can be mentioned here are economics and education. The economic reason is as simple as the fact that what one earns from writing is very little. I remember a conversation with Bambang Bujono, a senior Indonesian visual arts writer. At that time, we tried to calculate the honorarium a freelance writer got from a well-known publication in Indonesia (one of the highest-paying, of course). Then we compared it with what a writer from Jakarta needed if they wanted to visit an exhibition in Bandung. Our conclusion was that the honorarium did not even cover the accommodation and transportation.

Modern education in Indonesia has been teleologically self-denying since its inception. For Michael J. Sandel, the purpose of university-level education is merely to honour and reward academic excellence, and to fulfil a duty to society by setting an example and establishing ideals or ideas in society.[11] Modern education in Indonesia, which was first widely disseminated by the Dutch Colonials in the context of Politik Etis (Ethical Politics), already defied this purpose: their goal was very practical, namely to prepare a cheap labour force from the archipelago. For many Indonesians at that time, the opportunity to be educated and then work as a clerk in Dutch offices was a way to rise in social status; to become a priyayi[12]. As a result, people were more interested in the titles that came out of education and the educational institutions themselves rather than the knowledge they were acquiring. 'The important thing is to graduate quickly, get a diploma, then apply for a job.' We often hear such jokes. This skewed goal of education continues to persist today. The following quote from Martin Suryajaya may illustrate the condition of educational institutions in Indonesia,

We have institutions but they are only pseudo-institutions: sometimes they act as educational institutions, sometimes as banks, sometimes as houses of worship, sometimes as dens of corruption, sometimes as places to play gaple. Nothing is certain and no one knows for sure.[13]

The question is, why did this happen? Above we have talked a little about the distorted aims of modern education brought about by colonialism. Martin Suryajaya and Hilmar Farid have speculated about the origin of this 'Silent Path' in the context of Indonesian writing and scholarship as a result of colonialism.[14] There is a cultural rupture, not only at the level of intangible culture but also at the level of tangible culture, caused by colonialism.

Let's try to look into this further. We'll start with an interesting excerpt from the novel Orang-Orang Oetimu. This novel tells the story of a village called Oetimu on the island of Timor in the Indonesian region over several decades, from the Portuguese colonial period to Indonesian independence. One of the characters is Am Siki, who has special Timorese magic. With his magic, he once killed many Japanese soldiers because they raped his horse. This is one of Am Siki's complaints in the novel,

Then Am Siki's chest became tight. He became sad because the foreigners kept coming and coming, but none of them wanted to learn to speak the language properly. It was always the Timorese who were forced to learn the meaning of the strange sounds that came out of his mouth; from Portuguese, Dutch, Japanese, to Indonesian.[15]

From Am Siki's grief, we can see how colonialism deprived people of language, their main tool of knowledge distribution. Timorese in the context of Am Siki had to abandon their language and learn new languages. In fact, it was through their language that the world around them was understood and their social way of life was formulated. As they learnt a foreign language and slowly forgot their native tongue, they lost the knowledge of their world.

In the context of the intellectual world, Amir Hamzah, as described by Hilmar Farid, narrated the disappearance of the Malay pantun along with the arrival of colonialism. All that was left was 'silence': 'After Malacca was destroyed by Alfonso's cannon, the spirit of Malay poets disappeared. Loneliness in the chest of the Malay child, extinguish the fire of poetry, dry the eyes of poetry.' All the spirit of literature (intellectual work) was lost because the source of inspiration and culture was also destroyed by colonialism. For example, in 1894, the Dutch attacked Lombok and looted hundreds to thousands of treasures and ancient manuscripts. [17]

In his book, Kesusastraan Kehancuran (Literature, Destruction), Martin Suryajaya problematizes this further. He sees it as the cause of the emergence of the motif of loneliness in Indonesian literature from the colonial era to the present day. Colonisers even changed and edited the culture of the archipelago, which over time was considered the original culture of the archipelago itself. 'What we call "tradition" today is actually a simulation of the past created for colonial interests', said Suryajaya.[18] At first, Indonesian intellectuals only felt the silence but did not realise it. Pramoedya Ananta Toer, according to Suryajaya, was among those who realised the reason behind the silence, behind the silent singing. Through his book Nyanyi Sunyi Seorang Bisu (The Mute Soliloqui), Pramoedya showed that the 'silence' was an impact of colonialism and neocolonialism. [19]

What is also important is how colonialism changed the medium of knowledge dissemination. After the Nusantara manuscripts were destroyed, colonisers introduced modern Western education which has its own 'components'. The letters of the archipelago were replaced with Roman letters, changing the method of learning, from the tradition of sitting together and talking into a cold, unidirectional classroom. Of course, like spoken languages, the writing system used by a particular society is rooted in its natural and social conditions. Unfamiliar components and mediums of knowledge dissemination also affect the embodied process of obtaining the knowledge. The lack of seriousness towards writing and reading activities I complained about at the beginning of this article has more or less been a result of the effect of an imposed writing system.

Back to the Fate of Jurnal Karbon

How does the historical story above contribute to the reflection on Jurnal Karbon's journey? Earlier it was mentioned that Jurnal Karbon is not a knowledge distribution tool in itself. It's more accurate to see it as an effort to experiment with various media of knowledge distribution: from printed journals to online magazines, videos and radio talks. But if we open the six print editions of this journal, we will find a form of writing that is similar to what Jurnal Karbon is doing today: radio talks. In each of the six issues, you will always find a transcript of a discussion or talk on a particular subject. It could be argued that the journal has been concerned with conversations from the beginning. Unconsciously, this emphasis on conversations came to the fore again when Jurnal Karbon in recent years has concentrated more on delivering talks via radio channels.

It is also possible, and this is again speculation, that the oral tradition of the archipelago speaks to its people in a more profound way. It's modern education that has made us forget and distance ourselves from it. The emergence of platforms such as Internet-based radio and podcasts may have raised the possibility of knowledge distribution similar to the oral tradition. Didn't human beings invent writing in the first place so that it would be timeless and immutable for passing on? In oral traditions, the transmission is done by word-of-mouth, from generation to generation, with the risk— which is precisely the peculiarity of the oral tradition itself—that there will be many variations. Recording and podcast technologies actually eliminate the occurrence of various variations. Oral speech can thus be heard today and anywhere.

In 2025, ruangrupa will be 25 years old. The same goes for Jurnal Karbon. Lately, Jurnal Karbon has been on hiatus, resting quietly and only occasionally releasing new material. Dirdho Adithyo, Bagus Purwoadi, Ayu Maulani and myself, the four people who are currently at Jurnal Karbon, have been spending most of our energy on other work at Gudskul Ekosistem. Jurnal Karbon seems to be sitting alone, waiting for us to tinker with it again. This article is just a spillover of memories and the result of leafing through existing archives. It may be a reflection, it may be a question, it may be a start for further change, or it could also not produce anything.

This article was first edited and proofread in English by Dirdho Adithyo.

Second-round English editing by Cindy Ziyun Huang.

Chinese translation by Jianyi Zou and Nie Xiaoyi.

Final proofread by Di Liu.

Notes

[1] Sinta is a journal accreditation system issued by the Ministry of Education and Culture. See https://sinta.kemdikbud.go.id/, accessed on December 17, 2024.

[2] Ronny Agustinus cs (eds.). Absolut Versus (Jakarta: ruangrupa), 2001, p. 53. I am not sure that the last art journal in Indonesia was Seniman. Perhaps when the early members of ruangrupa wrote the description of Jurnal Karbon, they did not count the 'academic journals' of the art schools. Or perhaps there were no art journals from academia at that time. Even if there were, sometimes academic journals didn't have much contact with practices that happen outside academia itself. As for the accuracy of the claim in the quote above, it needs its own research.

[3] Karbon (Cetak Urban Edition). Terbitan 2 – 04 / 2001. p. 2.

[4] Ardi Yunanto cs. Ruangrupa 2000 – 2015 (Jakarta: ruangrupa), 2015, p. 11.

[5] This does not mean that Jurnal Karbon is completely separate from the work of ruangrupa. From its earliest days until now, the connection has been inseparable. What I mean here is that the emphasis of the definition has shifted.

[6] Of course, ruangrupa's written work is not limited to what this article mentioned. There are many other books, catalogues, and websites produced by ruangrupa. What is presented in this article is the writings that, in my opinion, are the most relevant to Jurnal Karbon.

[7] Ardi Yunanto. “Hai, Bung!”, Bung! Edisi 4 Des 2012 – Jan 2013, p. 103.

[8] There is one Jurnal Karbon programme that has been forgotten on this timeline, namely the video coverage program entitled Tak Kenal Maka Tak Sayang (Do not know, do not love), a collaboration between Jurnal Karbon and Qubicle in 2015. No less than 10 videos of coverage and casual conversations about art and its ecosystem were discussed in the video. The videos present glitches to the influence of the zodiac on artistic endeavors.

[9] I should emphasise here that this does not mean that I see conditions in other countries as better. However, due to limited knowledge about similar issues in other countries, I focus on the conditions in Indonesia.

[10] Of course, this doesn't apply to all types of writers and all types of writing; there are certain genres of writing that are very marketable, and there are certain writers who can walk the high road.

[11] Michael J. Sandel. Justice: what's the right thing to do? (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux), 2009, pp. 191–192.

[12] 'Priyayi is a person who belongs to a layer of society whose position is considered honorable, for example, civil servants', KBBI Online. Accessed on December 18, 2024.

[13] Martin Suryajaya. Homecoming Alumni STF Driyarkara: Buku Program (Jakarta: STF Driyarkara), 2019.

[14] See Hilmar Farid, “Kesunyian sebagai Motif Utama Kesusastraan di Negeri Bekas Jajahan”, in Niduparas Erlang (ed.), Simposium: Pascakolonial dan Isu-Isu Mutakhir Lintas Disiplin (Rangkasbitung: Dinas Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Kabupaten Lebak), 2018. And Martin Suryajaya, Kesusastraan Kehancuran (Jakarta: Penerbit Velodrome), 2024.

[15] Felix K. Nessi, Orang-Orang Oetimu. (Jakarta: Marjin Kiri), 2022, p. 39.

[16] As quoted in Hilmar Farid, 'Kesunyian sebagai Motif Utama Kesusastraan di Negeri Bekas Jajahan', pp. 2-3.

[17] Hilmar Farid Setiadi, 'Rewriting the nation: Pramoedya Ananta Toer and the politics of decolonization'. PhD Thesis. Cultural Studies in Asia Program. National University of Singapore, pp. 74 – 82.

[18] Martin Suryajaya, Kesusastraan Kehancuran, p. 104.

[19] Martin Suryajaya, Kesusastraan Kehancuran, p. 125.

About the Author

Berto Tukan is a member of Gudskul Ekosistem, Jakarta. He is a writer and independent researcher who lives in Jakarta and also a part of Jurnal Karbon. In 2019 - 2021, together with several friends in Gudskul Ekosistem, he researched the development of art collectives in Indonesia. The results of that research can be read in the book, Articulating Fixer 2021: An Appraisal of Indonesian Art Collectives in the Last Decade (Yayasan Gudskul Studi Kolektif, 2021). His short story collection, Seikat Kisah Tentang yang Bohong was published in 2016 and his last poetry collection was Aku Mengenangmu dengan Pening yang Butuh Panadol (2021).

本文图片均由作者提供。

感谢吴作人国际美术基金会对本文稿酬的支持。

感谢通过“赞助人计划”支持《歧路》的个人与机构。

Comments