Revolution: The Foe of An Arrow Wound

- Shuyu Chen

- Aug 4, 2025

- 20 min read

Updated: Aug 27, 2025

*This text was translated from the Chinese version with the assistance of an AI translation tool.

All long nights are expectations within curses

All revolutions are ideals betrayed

—Bei Dao, 'Divergent Paths', 2023

After nearly three years of research and production, Revolution: The Foe of An Arrow Wound — a large-scale installation performance by Paper Tiger Theatre Studio — premiered on April 21, 2023, at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin. The project starts from the Qianlong Emperor's scroll painting, MaChang Lays Low The Enemy Ranks (玛瑺斫阵图) which came to Germany at the turn of the 20th century. By following the journey of an arrow painted in the scroll, the research looks at the boundaries of history, geography, and museums, and examines Stachel in Fleisch (thorns in the flesh) that lie beneath major historical narratives. The performance brought to life the ghosts wandering in the museum — bodies shot through with arrows of revenge — looking for the moment when these arrows could finally be pulled out in the ghostly time and space of theater.

Paper Tiger is a Chinese independent theatre collective that focuses on cross-cultural practice. As an architect and curator, I have maintained a loose but sustained collaboration with them for the last fifteen years. Revolution: The Foe of An Arrow Wound is my first full engagement as one of the core team members. After going through the entire process of research and production, I found it fruitful to reflect on my embodied practice at the intersection of curatorial experiments in contemporary art and post-dramatic theater, pondering on how 'exhibition' and 'performance' can inspire each other and break through boundaries together.

During the research phase, I introduced Jewish-Swedish artist Andreas Gedin as artistic advisor to join the team. His involvement brought another perspective and critical tension to this cross-cultural theater project.

At Qilu's invitation, Andreas and I took on a two-way writing task – I wrote from an insider's point of view while Andreas wrote as an observer. We aimed to create a cross-cultural context where our essays talk to each other, and our maps of the research-creation-performance journey would fill in each other's missing parts. What's more, we sought to explore the 'blind spots' in such an intercultural artistic collaboration – the hidden corners where translation can't reach or make things clear.

Since its premiere, Revolution: The Foe of An Arrow Wound had two reruns – in January 2024 and January 2025 – something that has never happened before for similar performance projects commissioned by the Humboldt Forum. The work was shortlisted and got an honorable mention for the 2024 Berlin Theatre Festival and is planned to perform in Shanghai this September.

Desert

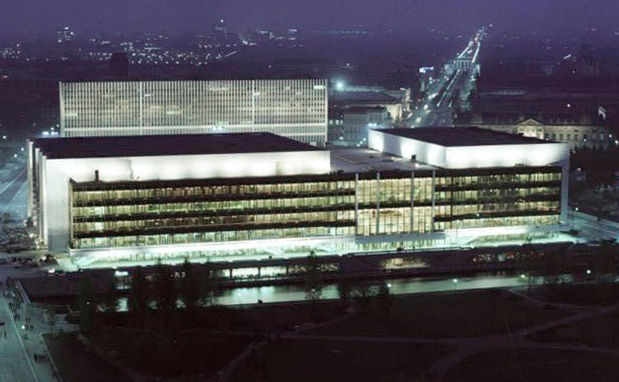

On the evening of October 7, 1989, inside the Palace of the Republic (Palast der Republik) at the southern end of Museum Island in East Berlin.

The former GDR's Politburo members were dining with international guests, celebrating the 40th anniversary of the GDR's founding. Meanwhile, a rally of nearly three thousand people was approaching the Palace of the Republic from Alexanderplatz. As the situation developed, the main guests, the Gorbachev couple, suddenly left the table and hurried to the airport. That evening's banquet had to end prematurely, and the prepared dessert was never served. It was a chocolate almond meringue sponge cake called 'Surprise'.[1]

About five weeks later, the Berlin Wall fell.

Asbestos

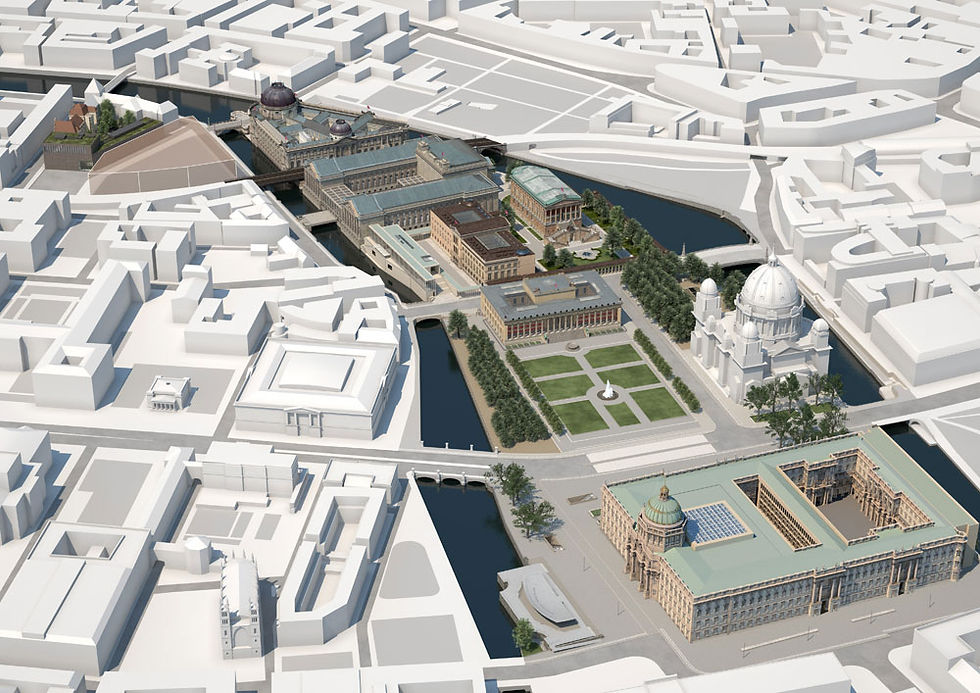

On the eve of German reunification in October 1990, the People's Assembly passed a law to close the Palace of the Republic because the building contained asbestos, a cancer-causing material. Demolition work began immediately, starting with removing the interior furnishings. After 2003, the Palace of the Republic in its semi-ruined state was opened to the public. Within the empty architectural body, many experimental urban cultural activities took place. In parallel, intense debates unfolded around how this wounded site in the heart of Berlin should fulfill its spatial mission- remembering the past while opening to the future. Beneath the foundations of the Palace of the Republic lay the ruins of another architectural symbol: the Berlin Palace, emblem of the German Empire, which had been destroyed during World War II. In 2006, demolition of the main structure began. Two years later, this most important landmark of the former GDR completely disappeared from the cityscape of Berlin.

In December 2020, a world culture museum was completed on the site and named the 'Humboldt Forum'. This museum covers 40,000 square meters and displays nearly 20,000 artworks and artifacts from Africa, Oceania, Asia, and the Americas. These collections belong to the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation(Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz; SPK), the Berlin Ethnological Museum(Ethnologisches Museum Berlin), and the Museum of Asian Art (Museum für Asiatische Kunst). Many of them came directly or indirectly from geographical expeditions, colonial expansion, and war plunder during the German Empire period. It's worth noting that during World War II, Soviet forces also removed substantial collections from German museums as war compensation.

The Humboldt Forum is the museum for displaying these collections; the research systems of the above-mentioned museums still maintain their independence. An important part of the Humboldt Forum's own research and exhibition mission starts from its site memory, grounding further discussion about memory and identity in-between culture, political and social changes.

In fact, in any palace museum, we can easily see that almost all triumphalists have a severe collecting addiction. If land and resources are these predators' main course, then artworks are the 'dessert'. Looting and plunder becomes a carnival. Commissioning artists to produce symbols of power perhaps helps calm their deepest fears. They need to show off their military achievements and establish deterrence. For them, art becomes the tool to rewrite history and identity. Additionally, artworks and artifacts serve as diplomatic gifts to make peace and build political friendships. When governments change, these objects often end up in museums as witnesses to history.

James Joyce wrote in Ulysses: 'History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.' Today, as visitors step into this site and enter a spatial narrative woven around these collections, they also enter a 'dream within a dream' of war history and art history. After being torn down and rebuilt again and again, the existing semi-archaized modern architectural body seems to contain another kind of asbestos – memory elements in constant decay within the sedimentary layers of history. They seep silently into the purified museum air, rising through each level of exhibition halls, until they drift out from the reconstructed imperial dome atop the Humboldt Forum into the Berlin sky, prompting further public questioning.

We

The Humboldt Forum has been actively seeking new approaches to address public criticism since its opening, looking for various methods to redefine what the collections mean to the public. Among these efforts, inviting cultural outsiders to perform inside the museum and encouraging the public to think and discuss differently is an important strategy by the Humboldt Forum's Public Program department. In early 2019, after watching a performance by Paper Tiger Theatre Studio in Beijing, Jan Linders, project leader of the department, invited them to collaborate.

In summer 2019, Paper Tiger's founders Tian Gebing and Wang Yanan moved to Berlin. For an independent theater studio that had always existed outside China's official theater system and used theater as a way to re-enter reality, it was an important turning point for Paper Tiger to enter the German cultural scene as outsiders. What is the difference between being an outsider in two completely different cultural contexts?

Paper Tiger's move to Berlin also changed the host-guest dynamic in cultural exchange. Earlier, when they were based in Beijing, German dramaturg Professor Christoph Lepschy was invited by the Goethe Institute in Beijing to come and work with Paper Tiger in a Chinese context. Then Paper Tiger was invited to perform at German theaters and festivals. The mutual hospitality - where each side takes turns hosting the other - creates the intertextual flow for cross-cultural collaboration. Now they're no longer visiting guests but need to find the way to host themselves and feel at home while being situated somewhere they'll always be foreign.

The 'we' in the following text refers to the research and creative team: the director, choreographers, dramaturg, curator, stage designer, artistic advisors, and translators. But this 'we' sometimes splits along gaps of language, cultural background, and circumstances when people have different ideas, work in different ways, or interpret rules differently. This constant back-and-forth of disagreement and coming together is unavoidable in any large artistic collaboration. The questions are: How can 'we' keep trusting each other through friendship when a long creative process inevitably brings crises? How can 'we' make decisions together while maintaining the integrity of each voice?

We chose that arrow shot from three hundred years ago, and simultaneously chose to stand at the end where the arrow flies toward us.

Arrow

7 PM, April 21, 2023, first floor hall of the Humboldt Forum.

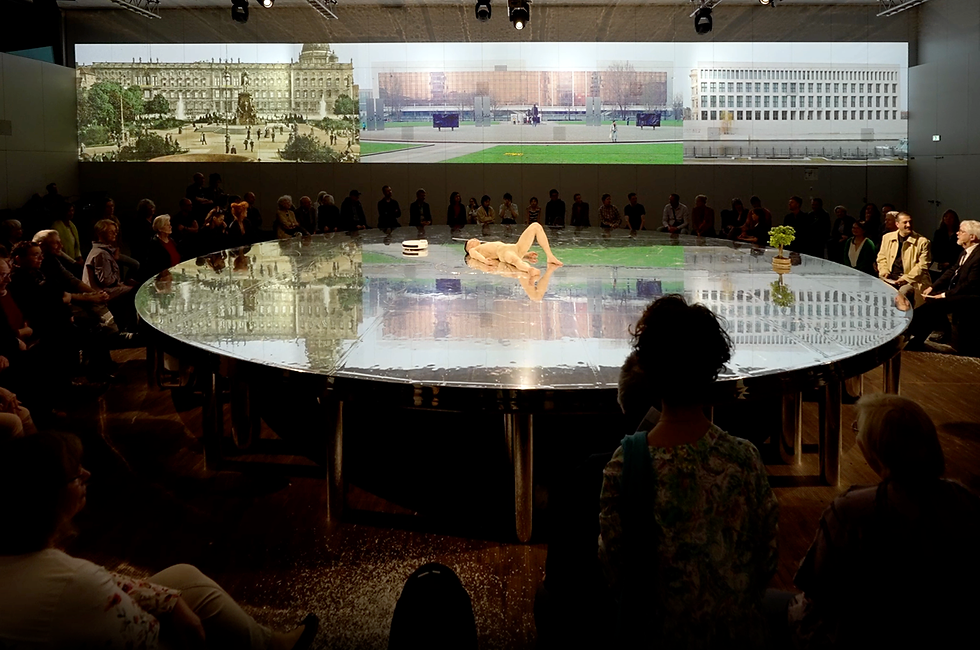

Revolution: A Foe of An Arrow Wound unfolded around an 8-meter silver reflective round table with one hundred and twenty guests in attendance. The performance began with the prologue, 'The Emperor's Masquerade', and consisted of three acts: 'The Palace', 'The Black Market', and 'The Museum' . These acts depicted the historical journey of the scroll painting, MaChang Lays Low The Enemy Ranks, illustrating its origin, displacement, and the display location.

In 1759, following the campaign to quell a rebellion in the far western territories of the Qing Empire China, the Qianlong Emperor ordered his Italian court painter Lang Shining alias Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) to make a victory painting. Facing the emperor's urgent command, Castiglione depicts the dramatic scene against a blank background and places the focus on the arrow that hits the rider in the back: the enemy's hand slackens in pain, his spear drops, he slumps forward, his hat slips from his head. As the key element that defines the memory of victory, the deadly arrow was no longer merely a weapon of war — it became a symbol of imperial triumph, a political artwork enshrined in the Hall of Purple Light (Ziguang ge) at the emperor's winter palace.

However, its association with martial splendor was short-lived. At the turn of the 20th century, the Eight-Power Allied Forces, led by Germany, invaded China. The palace was looted. Along with many of the emperor's collection, the scroll of the painted arrow may have been taken out of China directly or circulated on the black market in Beijing. Crossing continents and centuries, it transformed from glory to shame, from a war trophy to a traded piece of art, and eventually found its way to another palace — now a museum — the Humboldt Forum in the centre of Berlin.

In a sense, the entire project's research work was organized around such a symbolic arrow. As we trace its trajectory, a fractured map emerges, incomplete and composed of fragments: the memories of the conquered, the silence of the defeated, and ghostly whispers lingering at the edges of history, geography, and the museum.

Gradually, more broken arrows and 'the defeated' struck by history's arrows gathered toward us. They hibernated in the artifacts that traveled across the seas and deserts. Unlike those objects authenticated by art historians and settled on podiums or in glass display cases, they only belong to the hidden spaces of various silences. They wander outside the display system, as the uninvited and unseen, the ghosts between the guests and the host. Inside their grotesque body — just like the museum itself, if we could imagine the building as a kind of body — there are arrows that could not be pulled out by themselves. It causes occult bleeding and hidden pain.

In this reading and imagination, the fractured map of the arrow's trajectory that emerged during research became our dramaturgical vision for the performance – the homeless war ghosts wandering in the museum, with fragments of history that have nowhere to belong being scattered by a storm from the land of oblivion, swirling into an unstable circle that enveloped us.

Round Table

Such a silent and restless force field, or rather, a magnetic field where ghosts manifest, is the spatial-temporal concept of this installation performance.

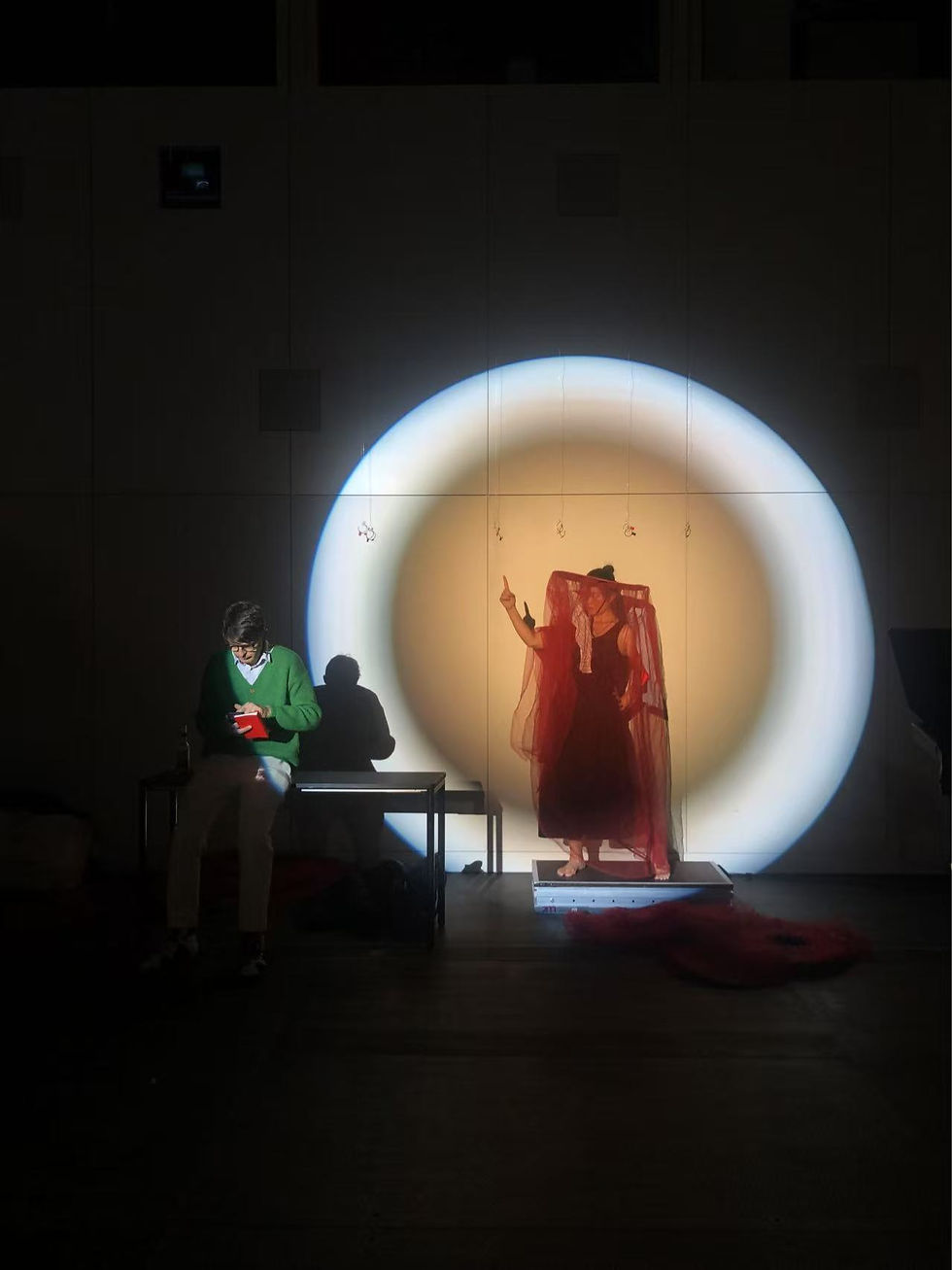

It is first a spatial object – the stage at the center of the site as a round table with an 8-meter diameter covered in mirror-reflective film. The table invites the audience to be part of the performance. There is no fixed seating in the hall; from the moment people enter the space, they enter a state of wandering and gathering. The performance begins with a masquerade, where audiences can take red wind-veil hats from the wall, wrap themselves in semi-transparent gauze robes, and step to the live DJ's experimental music into what feels like a black market hidden deep in history. Performers wear the same gauze robes, carrying silver trays filled with fake antiques and chocolates, weaving through the crowd to chat and sell.

As a performance held within a museum, the round table serves as a platform for both 'exhibiting' and 'performing'. It grounds us to raise a series of questions about 'body' and 'performance': Is the 'performative body' a conceptualized exhibiting object in contemporary art, or the central subject of a theatrical event? What are the differences between the viewer and audience in these two states? How do we shift the 'objects' situated in the museum's spatial power systems through this installation-performance? How can these exhibiting objects that are serialized in exhibition spaces, interpreted by labels, and strictly protected by viewing distances become 'props' that are appropriated, parodied, and touched in theater? How do 'objects' and 'bodies' form new relationships of possession in performance, haunted by the ghosts that inhabit the museum? How do images, sounds, symbols, discourse, light, and various technical means entering theatrical space lead us into history's nightmare? What triggers the possibility of awakening?

The concept of the round table as a stage comes from a historical photograph we discovered during research. It showed the negotiation table set up in January 1973 for signing the Paris Peace Accords to end the Vietnam War. According to records, deciding just the table's shape and size took six months, but ultimately this enormous round table successfully broke the deadlock among four opposing parties who couldn't sit face-to-face in pairs. In the historical photograph, it truly resembles an 'international political stage'. When those masters of patriarchal power sat around the round table bargaining for peace and deciding world fate, countless war ghosts seemed to wander on that empty tabletop.

The image prompted us to wonder: how power, performance, and historical trauma intersect around tables where life-and-death decisions get made. Around this giant round table, above and below, who hides in roles, performing cautiously? Who appears to be the audience but secretly observes and manipulates? And who, as themselves or dangerously exposed, performs radically and fatally?

We also turned these doubts and questions on ourselves, on this mirrored round table flickering under stage lights. The table creates enormous pulling force—a circle where bodies, objects, memories, emotions, and thoughts keep gathering. But as a stage open in all directions, it also constantly pushes outward, like the halo of light around the table that both focuses and spreads.

As performance events emerge from the dark spaces around it, and audiences come together and drift apart, the linear time of traditional storytelling becomes reoriented around the table. We intend to use stealth, slow infiltration, and lingering presence to create a spatialized temporality that swirls around the table, placing the audience in a haunting simultaneity where the ghostly past and the disjointed now merge.

Ghost

They won the war, yet lived as ghosts possessed by the defeated.

Consistent with Paper Tiger's approach, the creative process deliberately eschews traditional script-based dramaturgy in favor of what Hans-Thies Lehmann terms 'textual landscapes'. We employs found texts accumulated during research as performative materials, and through rehearsal as research, performers engage in somatic transformation of textual fragments, generating what we might call "performance texts" - dramaturgically connected events that emerge from the intersection of body, text, and space.

Although theater directors are still viewed as the soul, or central figures of today's theater production, in this performance, the performers are the spiritual mediators who manifest the ghosts that haunt the museum and the performance. Based on materials gathered from research and dramaturgical concepts, director Tian Gebing and choreographer Wang Yanan selected eight performers connected to history, objects, and the Humboldt Forum. Most of the artists and performers came to Germany as immigrants, carrying their own burdens of displacement and uprootedness.They are:

Ukrainian dancer Oksana Chupryniuk, who came to Berlin after the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, trained rigorously in ballet from childhood with very unique creative power;

French contemporary dancer Simon Chatelain, who loves street dance and skateboarding;

A young dancer from Taiwan, Lee Yi-Chi, who is small and agile;

A somewhat sleepwalking Indian dancer Raul Aranha;

Drummer Hu Shengnan, who works for the Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin;

A Japanese DJ living in Berlin, Suzuki Mieko, who DJed at the performance site;

The last two are Ariel Nil Levy, a queer performance artist from Israel who has lived in Berlin for many years with rich improvisational experience; and Hans-Jürgen Schreiber, the restaurant manager of the former Palace of the Republic. He is introduced to Paper Tiger by Jan Linders, and Hans-Jürgen was the first performer that joined this project and one of our research phase interviewees.

These performers were in place three months before the premiere, when we officially signed the performance contract with Humboldt and began theatrical creation work. Before this, our research phase is funded by one of the German national cultural foundations.

Among the eight performers, only the last two delivered spoken text, with Hans-Jürgen performing as himself—his appearance constituted a documentary theater element embedded within the performance. Ariel's performance navigated between triple identities as emperor's ghost, art historian, and journalist, requiring improvisation within a structured dramatic framework. The development of the 'emperor's monologue' became a significant creative challenge in this devised work.

During rehearsals, Ariel did a lot of improvisation on exploring what the Emperor was thinking, based on research materials provided by us and his own daily-life experiences as a queer performance artist. We recorded these sessions and translated them from English into Chinese, through collective editing, we created the Emperor ghost's monologue. It was translated back into English and brought back to the rehearsal room to work on more. This back-and-forth process went on through all the technical rehearsals, with the Emperor's text constantly being revised between Chinese, English, and German.

The challenge of performing stream-of-consciousness material in a semi-autobiographical mode became a central dramaturgical tension within the creative team. From my personal perspective, the performer—an artist good at improvisation—gradually lost his confidence and almost became a puppet actor chased by dramaturg to memorize lines. But he ultimately relied on his own performance instincts to create compelling expressiveness on stage. At the end of the year, the performer of the Emperor was unable to continue due to a scheduling conflict. Jan Linders recommended theater actor Thomas Halle as his successor.

Hijacking

Since the project started in early 2021, I went to the Humboldt Forum many times, spending hours in the Chinese Qing Dynasty Court Art exhibition room where MaChang Lays Low The Enemy Ranks was occasionally on display. I took in everything: how the space was arranged, how they grouped the objects, the details of the exhibition design, the labels, the timing of video clips, the lighting, and how visitors, the security guards and educators moved around. And I also got some chance to talk to Dr. Birgitta Augustin, a researcher and curator at the Museum of Asian Art who runs this exhibition hall.

When I read the German-English exhibition introduction and short text labels around the space, an idea of collectively rewriting the exhibition labels and making a small booklet for the performance came into my mind.

In this book, we understand the act of keywords writing as ghosts that take the form of absence and erasure, seeking to take over the official narratives inscribed on museum labels. Our collective writing takes up a particular genre of ancient Chinese literature that arises from left-over or marginal history. A notable example is Liaozhai's Records of the Strange (聊斋志异), a Qing dynasty collection of ghostly tales by Pu Songling (1640-1715), who called himself the 'Historian of the Strange' (史异士). He combined retelling, rewriting, commentary, and fantasy to tell uncanny stories that critique and reimagine the social structures of his time. Kafka's fascination with Liaozhai's Records of the Strange, noted in his diaries, further bridges the power of the 'strange' across cultures. His writing also built a Kafkaesque bridge toward what Deleuze and Guattari later defined as 'Minor Literature'.

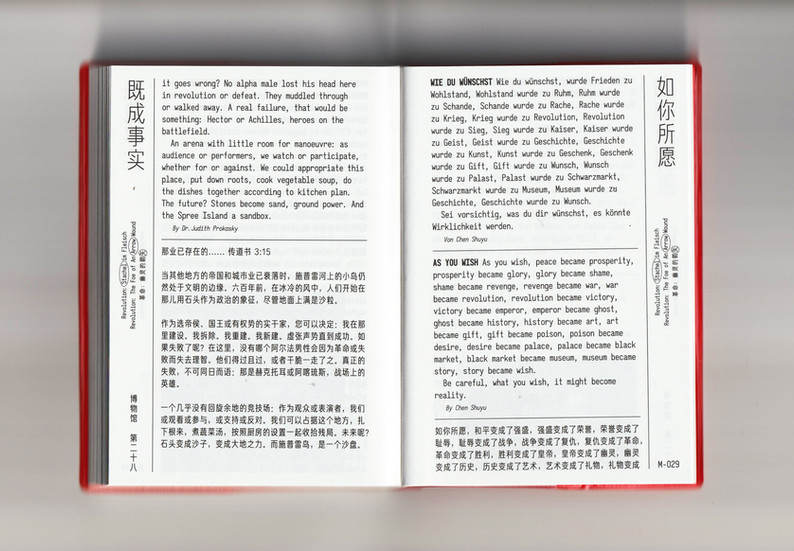

The Book of Arrow, 2023, graphic design by Our Polite Society

The 'Book of Arrows' is a 'dessert' made for the round table night, also a little gift for audience to bring back home. I still remember it was Jan Linders' idea for the timing of giving it out. As the performance got close to the end, audience was still caught up in Hans-Jürgen's story of going with the former East German Premier to visit China in the 1980s – to thank the Chinese host for its warm welcome and celebrate the strengthened political friendship, the chef team from the Palace of the Republic made a banquet in the Great Hall of the People with ingredients flown in from Germany to host both countries' leaders. While the background music full of memories from that time slowly got quieter, Hans-Jürgen and the 'emperor ghost' who dressed up as a journalist started giving out the 'Book of Arrow' to people sitting around the round table. At this moment, performers slowly walked onto the tabletop from the crowd, quietly sitting around the Asian performer who had been lying still in the center of the round table, holding an arrow in his mouth for a long time. He finally got the chance to 'let go', struggling to get up, slowly dropping the arrow from his mouth into a small hole in the center of the round table. When the arrow went down into the tabletop, the final performance 'Revolution Whispers', which came from Tracy Chapman's late-1980s song Talkin' Bout a Revolution, started.

In discussions with Tian Gebing, he defined this concept of rewriting exhibition labels as a hijacking of interpretation power, extending it as part of the performance's concept of taking action. We see 'hijacking' as a way to shift and reverse the established relationship between guest and host. Through 'hijacking', we open space for expression without applying for authorization or consent, breaking free from what appears to be an invitation but is actually an unequal power relationship. In Chinese cultural context, ghosts are endowed with powers of transformation and transcendence, forming subversive imagination against social structures. In the name of museum ghosts, we seek the fugitive paths beyond the narrative rights the Humboldt Forum granted us.

Qi Collection

One of the other concepts that complementes 'hijacking' is 'collecting qi' (采气). We borrowed this Taoist meditation method to create the flow mechanism between different worlds, cultures, and bodies throughout the performance. Possession and out-of-body experiences are qi's wandering; 'collecting' involves mutual absorption and mutual transformation, forming the basic rhythm of performance. At the end of the emperor's monologue, there is a brief declarative demonstration of the 'collecting qi' concept. When the emperor's ghost becomes immersed in his war memories, discussing how he guided court painter Giuseppe Castiglione in creation, Wang Yanan and an Asian male dancer circle around the emperor, pouring something into each other's throat with two teapots. The two dancers' performance is eerie and precise, while the emperor, in increasingly maddening hallucinations, questions why Castiglione's hands are trembling and claims to see that every war horse's face bears his own portrait.

Some audiences might notice that under the main title 'Revolution', the Chinese, German, and English subtitles differ. The English subtitle, 'The Foe of an Arrow Wound', was the translation of the initial working title '一箭之仇' (One Arrow's Revenge), derived from our first impression of MaChang Lays Low The Enemy Ranks. 'Ghost's Arrow' was the Chinese title the director, choreographer, and I reconfirmed at the end of the research phase. The German subtitle was a German idiom selected by dramaturg Christoph, 'Stachel im Fleisch' (thorn in the flesh), referring to barbs embedded in the body that cause bleeding and hidden pain. The naming across three different contexts can be counted as a kind of 'collecting qi' for 'inter-translation', like the symbolic arrow crossing through different histories and cultures.

This performance began with 'the foe of an arrow wound' and explored the historical and psychoanalytic dimensions of the 'thorn in the flesh' (Stachel im Fleisch), but the performance wasn't about revenge—it sought another way to begin. Theater exists in the liminal space between reality and dreams, the ghostly past and our disjointed now. All fixed identities become questionable here, all scripted dialogue risks betraying genuine emotion. Everything in theater works to awaken participants' physical awareness, connecting people and drawing them into the performance to create a flowing field of energy.

The late poet Ma Yan wrote in 'Learning to Play Along': 'Those who invent words, invent the future'. Derrida claimed: 'The future belongs to ghosts'. In this theater of cruelty, we watch an exhausted messiah lift the manhole cover of the storm's eye, using theater's most destructive force—humor—to shatter our last certainties.

Karl Marx compared revolution to a locomotive driving world history forward. Walter Benjamin offered a commentary on this idea: 'But perhaps it is quite otherwise. Perhaps revolutions are an attempt by the passengers on this train – namely, the human race – to pull the emergency brake.' (Walter Benjamin, fragment from The Arcades Project) History has gone off the rails; if we want to sleep peacefully, revolution is necessary. The project explored performances and actions related to revenge, atonement, and shame between history and reality, war and peace, but more importantly, we hoped this performance would become the chance to pull out the arrow unexpectedly. We would borrow the strength of ghosts as they move and dance—the flight of arrows might strike us between the eyes and make us, who have been accumulating so much for so long, suddenly realize something.

Haunted by the specters of Marx and other unrecognizable and desolate ghosts, the architectural remnants spread doubt and unease about reality among the city's inhabitants. However, for those who gaze at ruins and find fascination in incoherence and contingency, doubt and unease are the results of meditation on memory's natural imperfections. They serve as signs that history has truly penetrated our inner world, even though history remains the nightmare from which we constantly try to awake.

Hidden Pain

The future enters us long before it happens, in order to undergo transformation within us.

Rainer Maria Rilke

Theater, or theater in the true sense, is a festival where people who 'stand barefoot' gather. But even among those 'standing barefoot', one inevitably encounters multiple hidden pains of power at the boundaries between public and private.

Every theater project is an adventure undertaken by temporary collectives, involving both cooperation and competition between individuals and institutions. 'Revolution: Ghost's Arrow' was even more a theatrical action that crossed the turbulence between different cultural systems, resonating with war's ghosts within each other's historical traumas. When we use non-logical, imaginative, musical, dance, and dramatic methods in theater to break those 'father's laws' that attempt to control the world, we simultaneously remain trapped by such laws in reality—caught between invitation and restriction, freedom and safety, trust and suspicion. When this extended performance gradually withdrew from each participant's reality, how did individuals leaving the temporary collective handle the 'hidden pain' that entered their respective realities from the theatrical experience?

One day in April 2025, I received a painting from a stranger, it was one of the Tang Dynasty Zhaoling Six Horses rubbings made with ink-blowing technique in the late 1970s. In the scene, General Qiu Xinggong was extracting an arrow from the chest of his Western Region war horse Saluzi. Two years after encountering the arrow in Berlin, I encountered an arrow that had stopped sixteen hundred years ago, which made me revisit again a keyword called 'pull the arrow out' in the 'Book of Arrows'. I quoted a small story that Borges mentioned when discussing Buddhism in his late lecture series Seven Nights. I want to use it as the ending of this text:

A man has been wounded in battle, but he does not want them to remove the arrow. First he wants to know the name of the archer, to what caste he belongs, what the arrow is made of, where the archer was standing at the time, how long the arrow is. While he is discussing these things, he dies. 'I, however,' said the Buddha, 'teach that one must pull the arrow out.' What is the arrow? It is the universe. The arrow is the notion of I, of everything to which we are chained.

Notes

[1] The memory of this dessert comes from Hans-Jürgen. He was a former banquet manager at the Palace of the Republic who accompanied former GDR Premier Honecker on a visit to China in the 1980s. Hans is one of the performers in "Revolution: Ghost's Arrow.

Comments